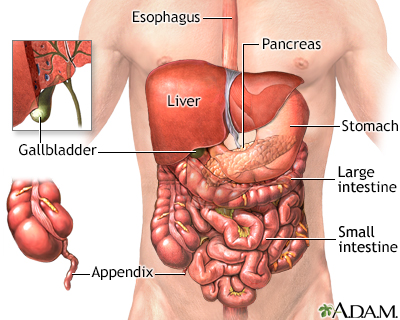

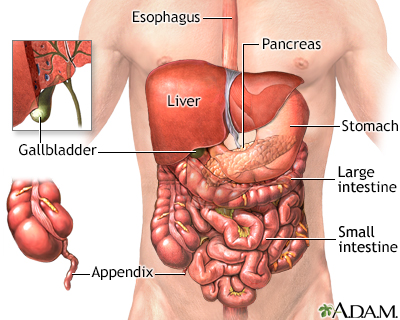

The process of digesting food is accomplished by many organs in the body. Food is pushed by the esophagus into the stomach. The stomach mixes the food and begins the breakdown of proteins. The stomach propels the food then into the small intestine. The small intestine further digests food and begins the absorption of nutrients. Secretions from the pancreas in the small intestine help neutralize the acid in the intestine to provide a proper environment for the enzymes to function. Bile from the gallbladder and liver emulsify fat and enhance the absorption of fatty acids. The large intestine temporarily stores and concentrates the remainder until it is passed out as waste from the body.

Food passes from the mouth through the esophagus to the stomach. The stomach churns the food and breaks it down further with hydrochloric acid and an enzyme called pepsin. The process of breaking food down in the stomach takes a few hours. From there, it goes to the duodenum, which the first part of the small intestine. Within the duodenum, digestive bile produced by the liver and stored in the gallbladder along with enzymes from the pancreas break it down more. Enzymes are chemicals that speed up the digestion of specific types of food. For example, the enzyme trypsin breaks down the protein in steak, and lipase helps to break down fat. Humans don’t have enzymes to break down certain plant fibers, which is why they can’t be fully digested. The enzyme called lactase breaks down the sugar in milk. Sometimes, lactase is not produced by the body at all, or in insufficient amounts, making a person lactose intolerant. So, when a person who is lactose intolerant eats ice cream or yogurt, the digestive system gets bloated and expels gas. Once everything is broken down, the small intestine absorbs the nutrients the body needs. From there the nutrients go into the bloodstream and to the liver, where poisons are removed. Undigested food and water continue through the small intestine and go into the large intestine, where water is reabsorbed. Then, at the end of the line, feces are eliminated through the rectum and anus.

Living with ulcerative colitis can be a constant gamble. You run to the grocery store, hoping this won't be the day when your disease flares up. You might get lucky, or your disease could hit again in the middle of the store, leaving you in a search for a bathroom. Let's talk about ulcerative colitis. Ulcerative colitis is a type of inflammatory bowel disease. It's caused by a malfunction in the body's immune system. Normally, the immune system protects against bacteria and other foreign invaders. But in people with ulcerative colitis, it mistakenly attacks the rectum and intestines, causing them to swell up and thicken. As a result, people with ulcerative colitis have bouts of severe abdominal pain and diarrhea. They can lose weight without meaning to. If you've been experiencing any of these symptoms, your doctor can test for ulcerative colitis with a colonoscopy. Your doctor can take a sample of your intestines, to diagnose ulcerative colitis and check for colon cancer, a risk associated with ulcerative colitis. Medicines can help with the symptoms of ulcerative colitis. There are medicines to control diarrhea, and pain relievers to help with the abdominal cramps. There are also medicines that quiet the overactive immune response that causes ulcerative colitis. Changing your diet may help control your immune system from attacking your intestines. Changing your diet can limit diarrhea and gas, especially when you're having active attacks. Your doctor may recommend you eat small meals throughout the day, drink plenty of water, and avoid high-fiber foods and high-fat foods. You may feel worried, embarrassed, or even sad or depressed about having bowel accidents. Other stressful events in your life, such as losing a job or a loved one, may make your symptoms worse. Your doctor can help you manage your stress. If your symptoms are severe, surgery to remove your large intestine may be the best way to cure your ulcerative colitis. If you're experiencing any ulcerative colitis symptoms-like stomach pain, diarrhea, or unplanned weight loss, call your doctor. Although surgery is the only cure, treatments can relieve some of the uncomfortable symptoms, and help you to lead a more normal life-free from the constant stress of having to search for the bathroom.

If bowel sounds are hypoactive or hyperactive and there are other abnormal symptoms, you should continue to follow-up with your provider.

For example, no bowel sounds after a period of hyperactive bowel sounds can mean there is a rupture of the intestines, or strangulation of the bowel and death (necrosis) of the bowel tissue.

Very high-pitched bowel sounds may be a sign of early bowel obstruction.

Most of the sounds you hear in your stomach and intestines are due to normal digestion. They are not a cause for concern. Many conditions can cause hyperactive or hypoactive bowel sounds. Most are harmless and do not need to be treated.

The following is a list of more serious conditions that can cause abnormal bowel sounds.

Hyperactive, hypoactive, or missing bowel sounds may be caused by:

Other causes of hypoactive bowel sounds include:

Other causes of hyperactive bowel sounds include:

Contact your provider if you have any symptoms such as:

The provider will examine you and ask you questions about your medical history and symptoms. You may be asked:

You may need the following tests:

If there are signs of an emergency, you will be sent to the hospital. A tube may be placed through your nose or mouth into the stomach or intestines. This empties your intestines. In most cases, you will not be allowed to eat or drink anything so your intestines can rest. You will be given fluids through a vein (intravenously).

You may be given medicine to reduce symptoms and to treat the cause of the problem. The type of medicine will depend on the cause of the problem. Some people may need surgery right away.

Ball JW, Dains JE, Flynn JA, Solomon BS, Stewart RW. Abdomen. In: Ball JW, Dains JE, Flynn JA, Solomon BS, Stewart RW, eds. Seidel's Guide to Physical Examination. 10th ed. St Louis, MO: Elsevier; 2023:chap 18.

Landmann A, Bonds M, Postier R. Acute abdomen. In: Townsend CM Jr, Beauchamp RD, Evers BM, Mattox KL, eds. Sabiston Textbook of Surgery. 21st ed. St Louis, MO: Elsevier; 2022:chap 46.

McQuaid KR. Approach to the patient with gastrointestinal disease. In: Goldman L, Schafer AI, eds. Goldman-Cecil Medicine. 26th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2020:chap 123.

Last reviewed on: 10/20/2022

Reviewed by: Linda J. Vorvick, MD, Clinical Professor, Department of Family Medicine, UW Medicine, School of Medicine, University of Washington, Seattle, WA. Also reviewed by David C. Dugdale, MD, Medical Director, Brenda Conaway, Editorial Director, and the A.D.A.M. Editorial team.